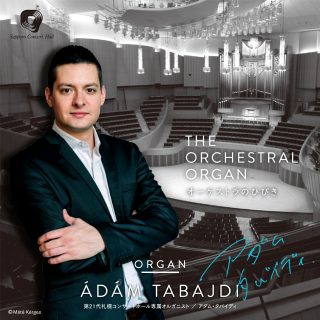

The Orchestral Organ

On his recording by the title ‘The Orchestral Organ’, Ádám Tabajdi shows the orchestra-like sound of the organ in a large overview of the history of music. The programme, which features original works inspired by the orchestra, arrangements, and transcriptions, attempts to illuminate the possibilities of this multi-faceted instrument from many aspects. The chronological order of the works from Bach to Bartók follows tangibly the process of change over the course of the history of music – the common denominator of the pieces is the orchestral sound ideal of the organ.

The CD was recorded in April 2020 on the Kern-organ of the Sapporo Concert hall ‘Kitara’.

J. S. Bach / M. Dupré: Wir danken dir, Gott, wir danken dir BWV 29: 1. Sinfonia

A. Vivaldi / J. S. Bach: Concerto in d minor BWV 596

W. A. Mozart / Zs. Szathmáry: Church Sonata No. 17 in C major K.336

F. Mendelssohn / S. P. Warren: “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” Op.61, MWV M13: Overture

F. Liszt / L. Robilliard: Orpheus S. 98

B. Bartók / Á. Tabajdi: Dance Suite BB 86a

The functional construction of the organ is very similar to that of an orchestra. There are different instrument families that are located on the different manuals; they can be used individually, but also in countless combinations of each other. Already from the early baroque period, one of the main aims of organ building was to construct an orchestral organ that can appropriately imitate the different instruments. Johann Sebastian Bach for instance, who not only knew the organ perfectly but also the orchestral instruments, often used various composing styles imitating the strings, the brass instruments or even the human voice in his organ pieces. Bach’s Sinfonia from the Cantata “Wir danken dir, Gott, wir danken dir” is the organ transcription of the first movement of his Partita in E major for violin solo. In the opening movement Bach creates an organ concerto in essence with the right hand playing the violin solo part in permanent semiquavers, while the left hand and the pedal play the accompaniment supplemented by a baroque orchestra. Marcel Dupré – a world-famous French organist of the 20th century – merged the orchestral accompaniment with the organ part, and thus the Sinfonia can be played alone without a supporting baroque orchestra.

Organ transcriptions have a long tradition in the music history. Thanks to the extended playing platforms of the organ, a lot of music with considerable performer requirements can be played on this single instrument. The manuals and pedals make it possible to play 6 or even 7 separate voices simultaneously, which makes it possible to render choir pieces, chamber music works, or even orchestral works on the organ. Even though the organ is a versatile instrument with countless amounts of playing possibilities, it also has some limits. Bach’s transcription of Antonio Vivaldi’s Concerto for double violin in D minor is a significant piece with regard to the history of the organ transcriptions. In the baroque era, organ composers almost never notated the exact registration (i. e., sound color expectations) in their scores, because it was self-evident for the performers; they clearly knew what was expected based on the style in which the piece was written. The Vivaldi/Bach Concerto in D minor is a perfect example of how the transcriber has to compromise to reach the original music. The concerto opens with a dialog between the two violins, which exceeds the normal original range of the organ keyboard. On the first pages of this organ transcription we can see Bach’s own registration instructions. Bach suggests that there are only 4’ stops on each manual with which the organist can extend the range of the keyboard with one more octave. After the opening, there is a great orchestral fugue, which would not be performable on a keyboard instrument without pedals. The middle movement is an Italian dance, a siciliano, which demonstrates the most expressive solo stops of the organ; while the last movement is a typical concerto grosso, a competition between two violins and the orchestra. In this case the second manual represents the soloists, while the first is the orchestra.

In the second half of the 18th century the role of the organ was de-emphasized, presumably partly due to secularization and propagation of movements against the church in society. Despite this however, organ music was present – maybe less spectacularly – and it was continuously evolving. Besides some works for musical clocks, the Church Sonatas of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart clearly demonstrate the classical period view of the organ. In his 17 church sonatas (sonata da chiesa) Mozart gave the organ an important role. In 8 of these sonatas the organ has an improvisation-like accompanying role, called basso continuo, but in 9 of them, the organ has a so-called obligato solo part, which means that the organ part is written down as in the original version of Bach’s Sinfonia. Zsigmond Szathmáry, the most important representative of the modern Hungarian organ music world, transcribed Mozart’s Church Sonata in C major in a very similar way as Dupré did with Bach’s Sinfonia: Szathmáry consistently inserted the orchestral instrument parts into the organ solo.

At the beginning of the 19th century the organ returned as an interest of the romantic composers and again became a popular instrument. This re-discovery is largely owing to Félix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, who reached back, not just to the organ, but to the work of Johann Sebastian Bach as well. The child prodigy Mendelssohn was 17 years old when he read William Shakespeare’s comedy A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The play made such an impression on the teenager Mendelssohn that he quickly noted his musical thoughts about Shakespeare’s fairy world. The brilliance of Mendelssohn’s Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream is clearly expressed in the following citation by the famous musicologist George Grove: “the greatest marvel of early maturity that the world has ever seen in music.” Even though in its musical language it is a purely romantic piece, it has strong classical roots – in the structure for instance, we can clearly observe the classical sonata form. The organ transcription was created by Samuel P. Warren, a co-founder and honorary president of the American Guild of Organists. Warren, who studied in Berlin and was about one generation younger than Mendelssohn, created an adequate transcription that assimilates well into the ideal sonority of the epoch.

Mendelssohn’s masterpiece projected forward the changing of a new musical trend: the appearance of program music, and by this, the style of the symphonic poem. This new style and tendency – which became popular among certain composers in the 19th century – means that the narrative itself could be offered to the audience either in the form of program notes, literary works, images or even just by the title of the piece, inviting imaginative correlations with the music. In his symphonic poem, Orpheus, Franz Liszt arranged the ancient myth of a legendary musician who could charm all living things, and even stones, with his music. According to the myth, Orpheus lost his beloved wife, Eurydice, but since he could not stand being without her, he traveled to the underworld. His music softened the hearts of Hades and Persephone who agreed to allow Eurydice to return with him to Earth on one condition: he had to walk in front of her and not look back until they had both reached the upper world. He set off with Eurydice following him, but in his anxiety, as soon as he reached the surface, he turned back to look at her, forgetting that he had to wait until both had reached the upper world. Eurydice vanished again, but this time forever. The organ transcription of Liszt’s symphonic poem by his colleagues and pupils could already be heard during his life. Now, we can hear the arrangement by the great French organist and professor, Louis Robilliard.

Bartók is one of the most important musical personalities of Hungary of the 20th century. He is well known as a composer, but his work as ethnomusicologist was maybe even more important from the viewpoint of Hungarian folk music. With his close friend, Zoltán Kodály, they started to collect and organize folk music of Hungary and its neighboring countries. This interest in folk music of the different countries and regions definitively determined the trend of Bartók’s oeuvre. Basically, folklore inspiration is highly appreciable in all of his works. He sometimes arranges original folksongs, but he frequently builds up his composition idea to certain folk-like phenomena. Bartók’s Dance Suite is one of the most outstanding pieces of this latter composition style. The central idea of this piece is an important philosophical idea that had been present from an early time in Bartók’s life. In the Dance Suite, Bartók casts into the music the ideal of all people becoming brothers. In the beginning movements, different nations present themselves: Hungary, Romania, Wallachia or the Arabic region. Between all movements there is a so-called Ritornello, which is a Hungarian-style melody, and which plays a narrative role until the end of the piece. In the last movement, all of the represented nations unite and fuse into one great round dance of the people. The organ transcription of this piece was a grateful task owing to Bartók’s clear and embraceable orchestration and the piano reduction by the composer himself. Even though the main objective of this transcription was to approach the original music as far as possible, as in the case of any transcription, a new piece was certainly born.

The CD will be available soon on Spotify and on AppleMusic. Until then, if you want a copy, please contact us at the adamtabajdi@gmail.com, or with the Sapporo Concert Hall at the hall@kitara-sapporo.or.jp.